Emergency rooms are places where, for the most part, people wait. The people who are really sick will see a doctor immediately but most people aren't really sick when they get to the ER. So they wait in the waiting room, they wait for x-rays, they wait for blood tests, they wait for medications. They wait for a long time and then they get angry and they get miserable. Staff people including doctors often don't help with these things either. The ER is designed to be efficient - to reach a medical decision without any frills. The doctors and nurses can be similarly efficient in their bedside manner. This is often for good reason - they usually have 15 other patients they need to assess and treat within the next hour or so and so they really can't stop to get your entire life story.

I worked 10 total weeks of shifts through four ERs in three major

Canadian cities. I also did about two weeks of shifts in an emergency

room in northern Manitoba during various family medicine rotations. I observed a couple things about how an ER functions over my ten plus weeks in these various emergency departments. I am by no means an expert but from my perspective the ER accomplishes two major tasks. First, it deals with emergent, life threatening cases that require medical intervention (hence the name emergency department). This isn't just the typical "I got hit by a car" kind of emergency but it also includes conditions that may not be emergent but require some sort of specialist intervention urgently.

As an example, I saw a case one time where a man had come in because of steadily increasing shortness of breath over a 6 week period. He was sitting comfortably in one of the stretcher bays when I examined him and looked perfectly fine. As ER docs like to say he was "in no acute distress" which often is code for "should probably not be in my ER". Nevertheless his history was concerning- he was losing weight and he had a long history of smoking. So we ordered a chest x-ray and lo and behold there was a giant white mass enveloping his upper left lung field. This was a man who needed to see a cancer specialist immediately.

This first role of the ER is to act as a conduit into the medical system. ER docs are the people who make the initial call about who needs to see what medical services and when. They stabilize patients, make a rough diagnosis and then send them to the service that needs to treat them. The ER makes sure that the guy who gets hit by a car is not going to die, they assess to see what bones are broken, and then they ship him upstairs to see an orthopaedic surgeon who sticks a metal rod in his leg. The guy with the lung mass is discharged after getting an order for a CT scan of his chest and a referral to a respiratory doctor the next day. People with severe abdominal pain are sent to see surgeons, stroke victims are sent to see neurologists and people with suicidal thoughts are sent to see psychiatrists.

This is the cool part of emergency medicine. Figuring out what is going on with sick people who haven't been seen by any other medical providers and stabilizing them if necessary. This is why emergency doctors go into emergency medicine. But the second role of an ER is way less cool. Whereas the first role is the stuff of television dramas the second role is like watching paint drying while listening to elevator music.

The alternate function that ERs fulfill is that of a glorified, twenty-four hour walk-in clinic. This means back pain, runny noses, medication refills, and sprained ankles. This is not to discount any of these legitimate health issues but it is to say that many people who are waiting in an ER are not the reason it gets its name.

The people who wait for hours are usually the ones who should see their family doctor but for a variety of reasons they come into the ER and sit and wait and then complain about the wait times. Its an issue thats been on the back burner for a while but flares every once in a while when some hack journalist, looking to earn a pulitzer, dredges up some sob story about a person who was stuck in the ER for seven hours and didn't even get their stubbed toe treated. And because most people in Canada have waited in an ER these stories resonate.

The standard medical system response to this is to put out press releases and interviews on how they're working to shorten ER wait times and make patients better off. There is a theory though that while they say all of these things, hospitals and regional health authorities (RHAs) don't actually care about shortening ER wait times all that much.

This is a theory that's deeply rooted in political economy and its a pretty interesting one. RHAs know that their funding is dependent upon people lobbying the government for increases. The best way to create this political pressure is to make people angry and upset that they can't get good health care. So the RHAs will deliberately starve (or fund below the optimal level) the services that they know will put the most pressure on government. Everyone has been to the ER and everyone hates waiting in the ER and so that becomes the most visible place where RHAs can generate political pressure for governments to fund them at higher levels. They really don't care about ER wait times because reducing them would mean less political pressure and less overall funding, or so the theory goes.

So how could one test this theory. The quick and dirty way to do this would be to see if RHAs with high wait times get more funding and when they do, do they then reduce ER wait times. Do they put their money where their mouth is?

To test this, I had to get data from a couple of sources. First I took wait time data from this CBC article which sources their data from a Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) report that does not seem to exist anymore. If you've had any interaction with CIHI in any way this incompetence is not surprising. The data runs from the 2008/2009 to 2012/2013 fiscal years.

A couple of things about this data; first, the measure that the CBC article uses is the wait time of the 90th percentile. This means that 90% of patients wait less time than this measure while 10% of them wait longer. It is also a measure of how long you are waiting before seeing a doctor. It does not include the amount of time afterwards for imaging or bloodwork or medical orders.

Further, this data is not a complete picture of Canadian RHA wait times. It includes all the RHAs of Ontario but beyond that the data gets spotty. There are a number of large centres that are included in the data though including Saskatoon, Regina, Winnipeg, Halifax, Vancouver, and Edmonton.

The second thing I collected was budget data from annual reports that each RHA in Canada file every year. They have all been taken from the websites of the RHAs and the measure that I use for all of the following is the total expenditures in an RHA over a given year. The collection of reports is available upon request.

To support this theory we need to do two things. First, we need to establish that RHAs look like they're using wait times to secure more funding. This would suggest they have an incentive to keep wait times high. Second, we need to establish that after they secure this funding it doesn't look like they use it to reduce their subsequent wait times. Then we can say that this theory is at least consistent with the facts.

First lets establish that RHAs with high wait times get more funding the year afterwards. Below is a plot of the change in overall expenditures in an RHA for the years of 2008/2009 to 2012/2013 versus the wait times in the year prior. As last years wait times increase there is a positive increase in the change in expenditures in an RHA. RHAs with higher wait times are getting more funding the next year. This is at least suggestive that RHAs are using long wait times to secure more health funding. For those in the know, a fixed-effects regression conditioning on the RHA also shows a positive relationship.

To support this theory we need to do two things. First, we need to establish that RHAs look like they're using wait times to secure more funding. This would suggest they have an incentive to keep wait times high. Second, we need to establish that after they secure this funding it doesn't look like they use it to reduce their subsequent wait times. Then we can say that this theory is at least consistent with the facts.

First lets establish that RHAs with high wait times get more funding the year afterwards. Below is a plot of the change in overall expenditures in an RHA for the years of 2008/2009 to 2012/2013 versus the wait times in the year prior. As last years wait times increase there is a positive increase in the change in expenditures in an RHA. RHAs with higher wait times are getting more funding the next year. This is at least suggestive that RHAs are using long wait times to secure more health funding. For those in the know, a fixed-effects regression conditioning on the RHA also shows a positive relationship.

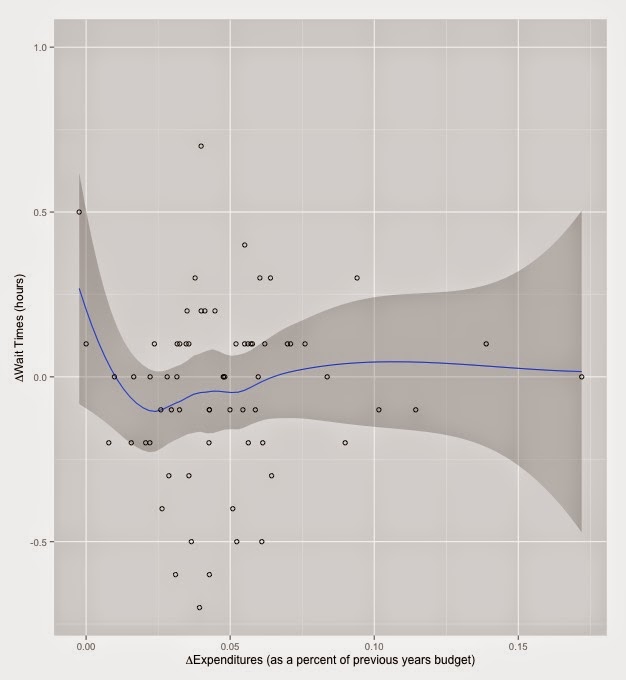

Now to make an argument that once the RHAs get this funding they don't reduce ER wait times with it. Below is a figure that graphs the change in expenditures versus the change in ER wait times. The relationship plotted is a LOESS regression (locally weighted scatterplot smoothing) and the dark grey area is the 95% confidence interval. Basically there is no relationship between changes in expenditures and changes in ER wait times. The exception is for a portion of the regression at about $30,000,000. I think this is likely due to chance rather than a real relationship.

But maybe this is the wrong relationship to be examining. This has no real regard for the size of the RHA and you would expect that very large RHAs would also have very large changes in funding simply because they are larger. An increase to the budget of Toronto's RHA is going to be larger than the increase to the budget of PEI's RHA. To try and control for this I've graphed the change in spending as a percent of the previous years budget (ie. (EXP_y1-EXP_y0)/EXP_y0). This will roughly remove overall size of the RHA (in expenditures) from being a confounder. Using this measure also shows little to no relationship between changes in expenditures and changes in wait times.

Maybe this is something that only applies in places where there are already high wait times. In RHAs that have high wait times do we see increases in funding translate into decreases in wait times? Using an arbitrary cut-off of RHAs that have wait times above 3.5 hours both fixed effects linear panel models and simple OLS models demonstrate no relationship between increases in funding and ER wait times in this subsample.

So it does seem that when an RHA has a longer wait time they get more funding. But when RHAs get more funding it doesn't seem like they use it to reduce ER wait times. Moreover, the places with high wait times that should be reducing wait times are not when they get more funding. This lends support to the RHAs don't care theory.

I doubt that this is something that would hold at any wait time level, especially very high ones. For example, the Grace hospital (in Winnipeg) has the longest wait times in the country at over 9 hours. Again, this doesn't count the time after seeing the doctor waiting in an ER. My guess is that this is a wait time that the Winnipeg RHA will not tolerate even if it means that they lose political pressure and associated funding bump. It does seem though that RHAs are willing to tolerate wait times of around three to five hours before emergency room patients will see an ER doctor.

I doubt that this is something that would hold at any wait time level, especially very high ones. For example, the Grace hospital (in Winnipeg) has the longest wait times in the country at over 9 hours. Again, this doesn't count the time after seeing the doctor waiting in an ER. My guess is that this is a wait time that the Winnipeg RHA will not tolerate even if it means that they lose political pressure and associated funding bump. It does seem though that RHAs are willing to tolerate wait times of around three to five hours before emergency room patients will see an ER doctor.

The use of this measure by CIHI and the RHAs is also a textbook example of how to lie with statistics. Note that they do not use the total amount of time that a person waits in the emergency room. They use time to see a doctor. The real time that a person spends in the emergency room is, without a doubt, far longer than what is documented here. I suspect the reason why this benchmark was agreed upon was to artificially reduce the wait times reported. This induces perverse incentives at the level of health care provider as pressure will be on doctors to reduce the time of first contact with a patient but not necessarily the overall wait time.

Finally, from a health systems perspective, if you buy this theory then the incentive is for RHAs to reduce the funding to ERs below an optimal level. They get more funding if they deliberately starve the emergency department. How should governments ameliorate this perverse incentive? One such strategy would be based on tying funding to actual future performance outcomes. If governments promised additional RHA funding bonuses based upon reductions in ER wait times this would provide the additional money that RHAs want if they actually get on top of the ER waiting problem. This would make it in an RHA's best interest to cut their ER wait times.